Down Under

Australia boasts 350 lighthouses that announce the coastline—and the continent as well. Gary Seale, in his book First Order: Australia’sHistory of Lighthouses, defines these as outfitted with an eight foot tall, five ton, first order Fresnel lens which beams light 15 to 20 miles out to sea. There are of course smaller lights which mark harbors, reefs, shoals, breakwaters or other hazards. All are known as aids to navigation (ATONs).

In October of 2024, my son Mark and I are in Australia where we plan to take the Indian Pacific Train from Sydney to Perth. Sometime in the mid 1980s Mark read Robyn Davidson’s book Tracks, the story of her trek with three camels from Alice Springs to the west coast of Australia. Ever since then he’s wanted to take the train across the Outback, and he was gracious enough to invite me to come along.

We hotel at the Sydney Harbour Hotel in the Rocks Neighborhood not far from the Harbour Bridge. We have a few days in Sydney touring the Concert Hall, attending an opera, eating at fancy restaurants. But best of all, for me, we take the ferry to Watson Bay to sketch lighthouses. On the way I snap a shot of the monstrous Fort Denison Light.

This chunky fella sits on what was Fort Denison on a tiny island in the middle of Sydney Harbour. Now a part of Sydney Harbour National Park, this has been a venue for New Year’s Eve parties and other celebrations. After the First Fleet arrived from London in 1788, some prisoners were kept here on bread and water, and the island became known as Pinchgut. Some were hanged here on the gibbet. Construction on the fort began in 1841, but the still operational Fort Denison Light wasn’t added until 1913 replacing the ten-inch gun which was mounted atop the Martello tower.

We disembark the ferry and hike out to the South Head now located in Sydney Harbour National Park. It’s a beauty, and there are but a few other spectators. I sit on a rather uncomfortable rock to sketch.

Construction of the Hornsby Lighthouse was precipitated by the 1857 wreck of the Dunbar off the South Head of the entrance to Sydney Harbour in New South Wales, Australia. Designer of the lighthouse is said to be colonial architect Alexander Dawson, although some sources promote Mortimer Lewis as the architect. The lighthouse is distinguished by its colorful vertical striping. In 2024, Port Authority of New South Wales restored the lighthouse.

Back at the dock we grab a taxi up to Macquarie Tower, a study in symmetry. Another rock to sit on but this one more commodious.

The first light to mark the entrance to Sydney Harbour, Mcquarie Tower, was designed and built by Francis Greenway, a brilliant convict architect—he’d forged a contract and his death sentence was commuted in 1813 to fourteen years transportation [that is transportation to Australia’s penal colony]. Governour Macquarie was so impressed with Greenway’s work that he pardoned him so he could be honored as a free man at the 1818 opening ceremony.

Greenway predicted that the sandstone used for the building was too friable and would crumble. Indeed, it did and although repairs were made, a similar replacement lighthouse was executed in 1863 on the same site right next to the old one which was then taken down. It’s the nearly 150 year old lighthouse we see today.

Just down the street is another lighthouse in the Vaucluse neighborhood. But it turns out it’s not a lighthouse at all, but rather the South Head Signal Station, a really fun arrangement of buildings to sketch.

The South Head Signal Station was designed by colonial architect Mortimer Lewis in the early 1800s when semaphore flags were used to send details of arriving ships. By 1858 a telegraph line had replaced the flags. A secondary function was to advise harbour pilots so they could meet incoming ships and guide them safely into the harbour.

In World War II the site was part of the military defense system and monitored all incoming vessels. However in 1942, three midget Japanese submarines, each with a two-member crew, entered the harbour, avoided the partially complete anti-submarine boom net, and attempted unsuccessfully to sink Allied warships anchored near Garden Island.

In the afternoon we take another ferry to the zoo so Mark can see koalas, dingos and kangaroos. On the way I snap a second photo, this time of the Robertson Point Light. The zoo does not disappoint us.

Robertson Point Light also known as Cremorne Point Light, an active ATON, is mounted on a rock and connected to shore by a footbridge. Together with its twin sister Bradleys Head Light they mark the entrance into Shellcove Bay. The reinforced concrete structures are a joy to behold.

On our last day we meet up with my daughter Kathi and her high school friend Terry. In the evening, we all take a harbor cruise. In the morning while Kathi and Terry set off for car camping in Tasmania Mark and I Uber to the Central Train Station and board the Indian Pacific bound for Perth.

Mark, Kathi and me on the water.

Crossing the Blue Mountains, we arrive in Adelaide and then on to Cook and finally the Nullabar Plain—where the tracks stretch in a straight line for 400 miles. Vast does not do justice to the enormity of the Outback.

Adelaide, South Australia.

The train is superb with a club car and dining car which has starched white table cloths and napkins, and excellent meals. We chat with Aussies, Tasmanians and a couple from Scotland.

I look out the window and don’t see any roadways nearby. Glad I’m cozy on the train. The flat bush country extends on either side, some hills some lovely skeleton like Eucalyptus trees, sand, shrubs, salt pans, and wheat, always changing. Ostrich at a distance, also kangaroos, camels, and sheep as we near the coast.

Eucalyptus trees, there are 800 species.

Perth is a good sized place with crisp architecture much better than back home. In the morning, we rent an auto and head south on AU-1 through Freemantle, Rockingham, Bunbury and Busselton to Cape Naturaliste Lighthouse. Mark talks me into buying First Order: Australia’s History of Lighthouses for AD 99.95—but with the exchange rate it’s 30 percent off.

Then down to Yallingup where we check into the Caves Hotel, a small, old but not too shabby, resortish place. This would have been quite the place back when. So peaceful here. Dinner at the hotel both nights.

American whalers frequented the west coast of Australia in great numbers during the 1840s. Three whalers sank in the same storm: the Samuel Wright, the North America, and the Governor Endicott. The first Cape Naturaliste Lighthouse was a wooden structure built in 1873 in response to at least a dozen other tragedies in the strong currents and dangerous reefs off the cape. The lighthouse we see today, positioned on a 300 foot bluff overlooking Geographe Bay, was first lit in 1904.

During construction a jar of mercury for the mercury float fell in the water. A sailor dived for it, but drowned in his attempt. More attempts were made but the mercury had sunk too deep into the sand—mercury is nearly 14 times heavier than water. William Tregarthen Douglass, a London based consulting engineer, advised sourcing the first order Fresnel lens from the Chance Bros of Birmingham, England.

In 1801 a French explorer named the cape for one of his ships the Naturaliste. Geographe Bay, he named after his other ship.

This section through the Cape Naturaliste Lighthouse shows more accurately how really stubby it is—the watchroom and lantern room above it are almost as tall as the 30 foot tower itself.

We’re off early in the morning to sketch the Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse. We lunch at Setters Tavern in Margaret River, and I feast on the battered West Australia Spanish Mackerel, toasted Scotch roll, lettuce, tomato and pickled red union. Then I search around and find a squashable bag to hold my huge newly purchased lighthouse book.

Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse was built in 1896 at the extreme southwest corner of Australia where the Indian Ocean Meets the Southern Ocean otherwise known as the Great Australian Bight. This time Douglass supplied conceptual drawings. Final plans were drawn up by colonial architect George Poole. In 1895 the barque, West Riding, left London with all the apparatus for the lighthouse, but it was lost at sea.

A smaller light was to be part of the structure, but it was abandoned because it could have caused confusion for mariners. With a focal plane of 115 feet, Leeuwin is the tallest lighthouse on the Australian mainland.

Chance Bros. supplied the cast iron spiral stair, and the bi-valve first order Fresnel lens which rotated on a mercury float pedestal, invented by Leonce Bourdalles, also provided by Chance Bros.

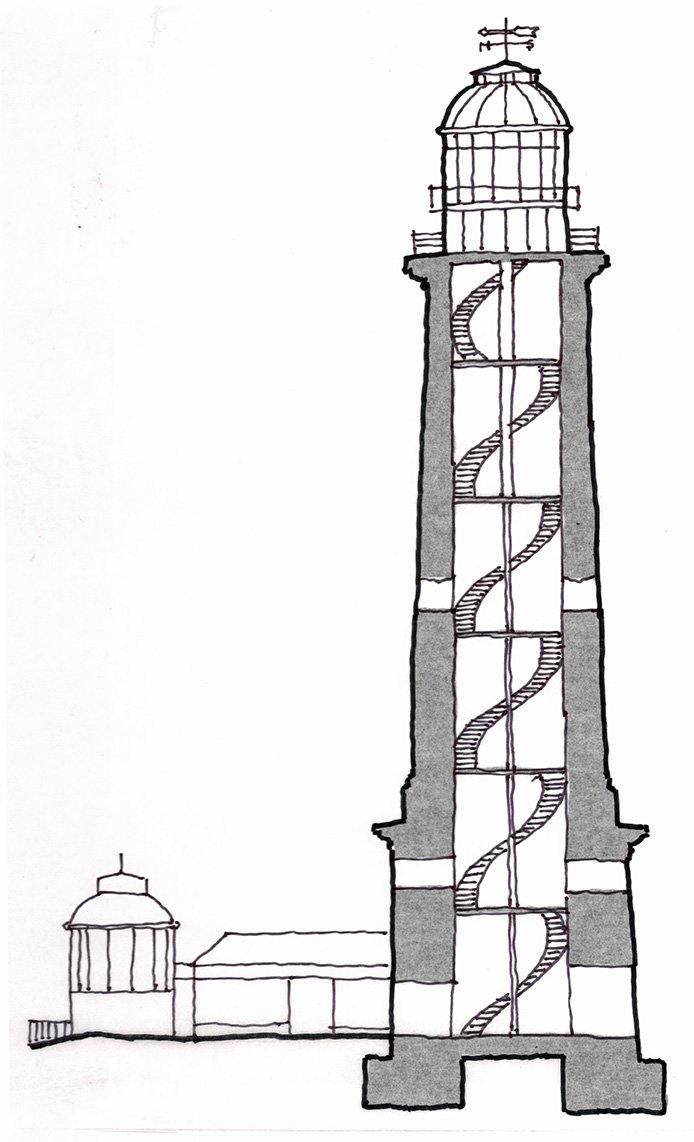

Here’s a section through Cape Leeuwin Lighthouse. Although the watchroom and lantern room are the same size is the Cape Naturaliste Lighthouse, the tower is much taller—about 120 feet. Note that in this picture the unbuilt secondary light is shown.

We’re up early to drive back to Perth, fly to Sydney, change planes and fly to Auckland, New Zealand, where we board the ferry to Waiheke. I take several photos of the Bean Rock Lighthouse. My Columbia classmate Brian Aitken and his wife Jenny meet us at the dock on Waiheke. They are native New Zelanders.

The 1871 Bean Rock Lighthouse marks the end of a reef in the Waitematā Harbour in Auckland, New Zealand. It is the only remaining example in New Zealand of a wooden cottage style lighthouse, and it is one of only a few remaining worldwide. It’s also the oldest wooden lighthouse and the only skeleton frame style lighthouse in New Zealand. It is owned, operated and maintained by the Port of Auckland. The light is named for Lieutenant Bean who assisted in the 1840 harbour survey.

Waiheke is a beautiful island and we drive around a bit, then on to Brian and Jenny’s cabin, which they built 50 years ago, still resplendent. After a couple nights at the cabin, we ferry back to Auckland and spend a night at their charming 150 year old family home. We have a lovely dinner at Sails—breaded scallops chili caramel, sriracha mayo, coriander Saint Clair Godfrey’s Creek Reserve Gewürztraminer. Everyone seems to know Brian and stops by to chat.

Just one of the fireplaces.

Next day Mark and I fly off to Blenheim where we board the Coastal Pacific for a beautiful train ride along the coast down to Christ Church. A day in Christ Church, then a drive out to the Banks Peninsula, a sketch of the Akaroa Lighthouse, lunch in Akaroa, and a successful dolphin cruise.

Akaroa Lighthouse was first lit in 1879 when coastal shipping was the principal form of transport and communication in New Zealand. A century later it was replaced by an automated light. The local preservation society raised funds to restore and move the badly leaking and deteriorating wood tower to a new site closer to town.

This is the front elevation of Akaroa Lighthouse, an intricate wood building, hexagon in plan.

In the morning, we hop on yet another train, this time the TransAlpine, and cross the island through the mountains.

On the TransAlpine.

In Greymouth everything is pewter gray: sky, sea, sand, and the US election, and it’s raining. On our 20 minute Uber ride to our hotel in Hokitika, I sweet talk the driver into a detour past the Hokitika Lighthouse.

Marine engineer John Blackett designed the square tapered costal Hokitika Lighthouse in the late 1800s. It was built near the jail on Seaview Hospital Hill, 90 feet above sea level. The jailer was, in fact, the first keeper. In the early 1900s the light was no longer necessary. The lighting apparatus was dismantled, the tower turned over to the hospital’s Mental Health Department, and subsequently restored.

There’s drama the last morning. Our flight to Auckland has been cancelled. We taxi to the Hokitika Airport where Mark gets new reservations from Christ Church to Auckland so we can connect with our Los Angeles flight. At the airport I’m standing by the curb when Mark sticks his head out and shouts, “Get in that car!” He’s finagled a ride with another party back to Christ Church.

Mark and I are squished into the back seat with another fellow. No convenience stops—a real bladder test for sure. We make the flight by the skin on our teeth, regain our lost day, and in 18 hours I’m home by three in the afternoon the same day.

This has been a spectacular three weeks. Good food, good weather, good camaraderie, and good lighthouses. If I had to move to a different country, it would be New Zealand.

Comments